Density Done Well

by Malcolm McCracken

“These are just future slums” is a common response to articles these days regarding medium or high-density housing. While these comments are far from the truth, they often stem from genuine concerns from residents about the change that could occur in their neighborhood.

The way we enable density and the actions we take to support the increased population, dictate the outcomes for our community. There is growing consensus that density is critical to the future of our cities. A recent Kantar public opinion survey found 49% of Aucklanders were positive about the new housing rules, with 32% being negative and the remaining neutral (16%) or unsure (4%). The debate is shifting to how to do density well.

There are two key components to density done well. The first is creating a positive built form, allowing higher density while protecting privacy, daylight and open space. The second is the supporting actions which ensure our medium and high-density neighbourhoods are vibrant and livable.

Density done well – A positive built form

The built form of our cities consists of the height, bulk (volume), the position on the site, orientation and shape of buildings. Historically, our built form has looked like one- or two-story buildings, standing alone on individual sites with some variety in shapes but largely simple rectangular housing.

As intensification occur, buildings typically become taller and bulkier, occupying more space on the site. This makes the position and orientation of buildings more important to protecting privacy, daylight and open space.

New Zealand’s historic subdivision patterns mean that most of our cities have narrow and long sites. When creating higher-density homes, developers look to maximise their floor area to ensure they can build as many homes as possible. Under current planning rules developers can typically build on 45-50% of the site.

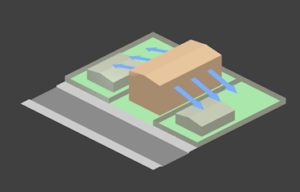

Deep sites, in combination with side and front yard requirements, and height in relation to boundary (HIRTB) rules mean that to maximise floor area, developers turn the building(s) to sit perpendicular to the street.

This leads to a longer skinnier building running deep into the site. To make practical units, this is then split width ways, meaning the units face outwards across the side boundary and into neighbouring properties.

Figure 1: Source – The Coalition for More Homes 2021

This is exacerbated by our side & front yard requirements and height in relation to boundary rules, which stop the development from maxing out the front of the site and orienting units over the street or back yard.

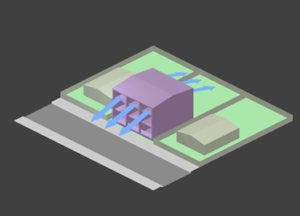

Figure 2: Source – The Coalition for More Homes, 2021

By removing the controls in the first 20m of the site, we incentivise developers to concentrate the bulk of development to the front of the site, leaving the rear as private open space. Units look over either public open space (the street) to the front or the private rear yard. This minimizes potential privacy issues and protects private open space and daylight access. It also creates positive interactions between homes and the street, similar to what occurs in many our most popular ‘character’ suburbs.

Figure 3: Removing side boundary controls allows different heights to sit comfortably side by side with units facing the street in Kingsland, Auckland.

Density done well – Vibrant urban environment

The built form is crucial for creating more pleasant and livable neighbourhoods. However, complementary actions to support the increased population are just as important. Most of these actions are the responsibility of local and regional councils.

The first is transport choice. More people means more trips around our cities. We need to provide viable and attractive alternatives to the private car, starting with frequent public transport, running at least every 15 minutes all day, every day. We need to ensure our bus stops and train stations feel safe and pleasant to use, make transfers easy and legible and allow for easy access by everyone.

We need to reallocate space on our streets to provide for safe walking and cycling for local trips. This means safe crossings and safe separated cycleways on our main roads, creating direct connections and serving the places people want to go.

Of course, there will still be some trips where a car is the most practical option. However, reducing the number of car trips will reduce congestion and mean we can free up parking spaces for more productive uses. As density increases, we need effective parking management to ensure kerbside space is available for those who need it such as tradies, deliveries and visitors.

A complementary and crucial action is the provision of car share. This is where people can book and use a car as it is required, down to an hourly or even half hourly basis. The provision of car share means households can reduce the number of cars they need to own. Research varies but each shared car is estimated to replace 5 to 15 private cars. This means space is saves both on-site and on-street through reduced parking requirements. It also can deliver significant savings for residents. Even for a new small car, you could end up having a fixed yearly cost of $5,000 (Automobile Association).

A supporting action to transport choice, which crucial to creating the vibrant neighbourhoods, is enabling mixed use development. This is key in a 15-minute city or complete neighbourhood vision, where you can access to your daily needs within a short ten-to-15-minute walk or cycle from your home. We should make small scale retail and commercial activities permitted activities across our neighbourhoods, to improve access to daily needs like local grocers, cafés and takeaways, hairdressers etc. close to where people live. The increased density supports this by increasing the potential customer base.

Improvements to the public realm are also needed. As our population increases, we must rethink the role streets play in our communities. Streets make up the majority of public space in our cities, yet the majority fail to provide any amenity for the residents of that street. Streets should be places to bump elbows with neighbours, spaces for children to play safely and the core network of greenery within our neighbourhoods.

In the Netherlands, there is a type of street called a woonerf or living street. Typically, narrow, kerbless and filled with greenery. These serve as the front step of many homes.

Figure 4: A woonerf (living street) in the Netherlands (Chris Bruntlett, 2022)

As our urban areas intensify, I would love to see many our residential streets retrofitted to deliver something similar. However, shifting kerb lines and drainage is where we see costs start to increase significantly. We need an approach that deliver changes that support the transition and value for money. For our Councils, we need a focus on planting more street trees and upgrading footpaths to meet current standards.

Going beyond this, we need to allow and encourage residents to rethink what role their street has the public realm. It’s awesome to see the Waka Kotahi Reshaping Streets package will allow for communities to manage their own streets for neighbourhood events. Imagine a summer, filled with neighbourhood barbeques, play streets for kids on summer holidays or some bat down cricket.

These events can be the catalyst for more permanent changes, designed for and by the residents of that street, like parklets and planters for community gardens. Supporting the increase in population and higher density living.

Conclusion

By creating a positive built form and vibrant urban environment centred on transport choice and improved public realm, we can not only support increased density, but deliver enormous widespread benefits. Density is key to supporting all of these and consequently creating awesome urban places. Who doesn’t want that?

In Part One of this series, Malcolm introduced the overall concept of density done well.

About the Author: Malcolm McCracken is a Transport Planner with Sustainable Transport Consultancy, MRCagney. Malcolm has diverse experience in transport planning & strategy, policy development, and transport and land-use integration. He is also currently undertaking a Masters in Public Policy at the Auckland University.