Natural Capital in our Region: How are we investing in nature and biodiversity? A look into the value and potential of our natural resources.

This is the third in a series of articles by WSP exploring issues and opportunities for the design and development of regions across Aotearoa New Zealand. Read on to hear about the importance of growing biodiversity or ‘Natural capital’ in our urban areas across the region.

What is a natural capital approach?

A natural capital approach is a way of putting nature at the centre of our world understanding as we look to better care for our natural resources, fresh water, oceans, forests, air, geology, soil, flora and fauna and all related eco-systems. We are the guardians of our places, natural and social. We have the opportunity to restore nature’s balance, to rewild cities, to green our neighbourhoods and support bio-diversity net gain across our communities. For instance, the wonder that is walking around Wellington at dusk, seeing starlings flying in from the suburbs to roost for the evening in their favourite trees, hearing the chorus of birds close out the day, is an invitation into the social life of birds – chirping and chattering away; and a beautiful reminder of our cohabitation.

There are more than 33,000 hectares of parks in the Wellington Region and many more in Horowhenua. You’ll be familiar with particular nature and biodiversity pockets around the region such as Zealandia, Otari-Wilton’s Bush, the Wellington Town Belt, Matiu/Somes or Kapiti Island. Nature and the myriad of its environments provide our cities, regions and places with an ecological type of wealth, and possibilities for both urban and backyard conservation. This natural wealth directly corresponds to growing biodiversity, well-being and social, cultural and environmental value. The question is, how do we measure this value and the potential of its uplift for our people and our places?

The term ‘natural capital’ is attributed to Ernst Schumacher, Economist, in his book ‘Small is Beautiful’, which was published in 1973 and sought to view the economic world differently. At that time (and arguably still today) natural resources were often considered to be infinite and used accordingly, whereas Schumacher reasoned, among other things, that they should be treated as valuable and finite.

The Wairarapa-Wellington-Horowhenua region boasts various examples of natural capital. The setting of Te Whanganui-a-Tara, situated between a rocky coastline filled with nooks and crannies and a forested backdrop forms a distinctive geographic identity. This is captured well in the stereotypical photos from the Cable Car or Mount Victoria Lookout (Tangi Te Keo, Matairangi i). These natural boundaries maintain clear edges for development; with the urban form, like water, trickling into the available gaps and the Town Belt providing the green lungs of Wellington City. However, the region’s natural capital isn’t just concentrated in the capital. The western coastline adds great amenity value and a strong tropical feel to the Horowhenua, while Porirua is sandwiched between the greenery and forest feel of the Belmont Regional Park and the cool blue hues of Te Awarua-o-Porirua Harbour. The Hutt Valley is characterised by the various regional parks and the Remutaka Ranges up above, as well as Te Awa Kairangi which flows through it and the Wairarapa is known for its waterways, wetlands and lake.

Nature as our biggest investment – why should we care?

Natural capital is a valuable resource as it provides important ecosystem services to humans.

“In some indigenous languages the term for plants translates to “those who take care of us.”

~ Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (2020)

Many of us can relate to the solace that was provided by local parks and greenery during pandemic lockdowns, or the sense of colour and life that the waterways and greenery add to our neighbourhoods. Urban green spaces are known to improve mental and physical health, as well as providing psychological relaxation and reducing stress, stimulating social cohesion, supporting physical activity, and reducing exposure to air pollutants (via photosynthesis – converting carbon dioxide to oxygen), and regulating temperature (World Health Organization, 2016). Various research documents and literature have explored the benefits and positive relationship between natural capital and health and wellbeing (Rugel, 2019) explores the connection between access to natural spaces and mental health outcomes across Vancouver. Using data from the Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health, it was shown that increases in the percentage of publicly accessible neighbourhood nature within 500m had indirect mental health benefits via increased neighbourhood social cohesion.

Research has found that natural capital in urban spaces is important for maintaining biodiversity within urban ecosystems (Strohbach et al, 2013). Even small increases of a few hundred square metres can increase bird populations. As urbanisation continues to expand, efforts directed towards the conservation of intact vegetation within urban landscapes could support higher concentrations of both bird and plant species (Aronson et al, 2014).

Toitū te marae a Tāne-Mahuta, Toitū te marae a Tangaroa, Toitū te tangata.

If the land is well and the sea is well, the people will thrive.

Is it enough?

Here we use the Wellington City Council Green Network Plan as an example.

During research carried out by Wellington City Council for the Green Network Plan, the ratio of green spaces within the city centre was assessed. It was discovered that just 9% of the 444.5ha that make up central Wellington City, could be considered green space (Wellington City Council, 2021). It can be difficult to define an ideal figure or percentage that represents an adequate area of green space in a city or town, however when compared to the 11% of the same city centre that is covered by parking lots and other off-street parking, a case can be made that the room for growth of the city’s natural capital lies within the centre.

Another interesting statistic found while developing the Green Network plan was, the ratios of tree canopy cover city-wide and within the city centre. When compared with other major cities including Auckland, Christchurch, Sydney, Melbourne, and London, Wellington has the highest amount of canopy cover, with 30.6% of the whole city being covered by tree canopy, however when this scope was narrowed down to just the city centre, Wellington City scored the lowest with only 5.12% of the city centre having tree canopy cover (Wellington City Council, 2021). These numbers match up well with the view we have looking out of the window of the WSP office which is located in the tallest building in Wellington City – while Wellington does boast a large amount of natural capital, these resources are not evenly distributed or accessible. There are indeed benefits to large concentrated areas of natural capital, especially when they are easily connectable to our communities or easily accessed by direct routes and public transport. However research suggests we can also optimize the benefits of our natural capital if it is consistently and strategically placed.

Photo top right: Intersection of Willis Street and Dixon Street. An example of urban canopy cover within Central Wellington

Photo: Near Intersection of Willis Street and Ghuznee Street. An example of a vast area of impervious surfacing featuring no nature within Central Wellington.

In an assessment of the state of the green space within the city centre, Wellington City Council’s Green Network Plan (2019) states, ‘The central city has a fragmented green space network with minimal cohesion and limited areas of ecological focus. There are significant gaps within the open space catchment, especially through Pipitea and Te Aro. There is also a significant lack of street tree planting which hinders greater connectivity between green parks, the Town Belt, Wellington Botanic Garden ki Paekākā and the Waterfront.’

In a report by the New Zealand Centre for Sustainable Cities, census data was used to assess the relationship between demographics and green spaces within the city (Blaschke, et al., 2019). The report found the current population’s access to greenspaces and their benefits were disproportionately distributed within the central city, and the disparities were likely to increase with population growth.

What can we do?

Within the context of the region, as well as New Zealand in general, the ongoing resource management and infrastructure reform, as well as urbanisation provide a fantastic opportunity to develop strategies and legislation to protect and enhance our natural capital. The formulation of new plans and legislation to replace the Resource Management Act 1991 and the hierarchy of policy statements and plans underneath it could include new policies, objectives, and rules to better protect existing natural capital, whilst the drive to improve stormwater systems provides a blank canvas to incorporate green infrastructure design.

Ongoing climate change provides various challenges which require natural solutions and thus the opportunity to expand our natural capital. Within the Ministry for the Environment’s (MfE’s) National Adaptation Plan for climate resilience, risks to coastal ecosystems, including the intertidal zone, estuaries, dunes, coastal lakes and wetlands, due to ongoing sea-level rise and extreme weather events have been identified as one of the significant risks to the natural environment. The obvious solution to these risks which has been recommended in the plan is the enhancement of ecosystems which are healthy and connected, and where biodiversity is thriving (Ministry for the Enviornment, 2022).

To deal with ongoing climate change, the New Zealand Climate Change comission have also recommendeded expanding native forests to build a long-term carbon sink (Climate Change Comission, 2021). The increased coverage indigenous trees will contribute to our climate change reponse as our indengious trees are known to have relatively high carbon sequestration rates.

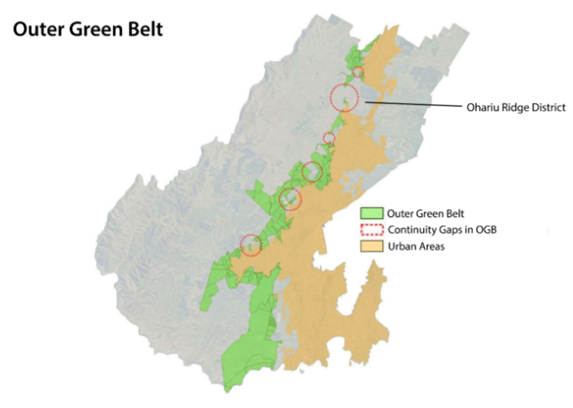

Government entities can also use their platform to run community-based initiatives for enhancing green space capital. An example of this is the Wellington Outer Green Belt which is an ongoing project run by the Wellington City Council in which the Council has been strategically acquiring land to form a continuous belt of vegetation reserves from the southern coastline of the region and up to the district border shared with Porirua City in the north (Wellington City Council, 2019). The aim of the project is to build and enhance this natural capital so that both the city can enjoy the wide range of conservation and social benefits. It will provide a native habitat for indigenous species as well as recreational areas and a sense of identity for Wellington City residents.

Figure 1: Map of Wellington Out Green Belt (Source: www.wgtn.ac.nz)

Is it a question of scale?

The World Health Organization recommends that we should all be only a maximum distance of 300 metres away from the nearest 1-hectare green space (World Health Organisation, 2016). Another emerging benchmark gaining popularity is the 3-30-300 rule which requires a ratio of 3 trees from every home, 30% tree canopy cover in every neighbourhood, and 300 metres from the nearest park or green space (Konijnendijk, 2022). These ideas for setting an ideal rule of thumb don’t necessarily require a shear abundance of green spacing, with a common theme emerging that sprinklings here and there add large value in the urban setting. It is encouraging that small improvements can have disproportionately positive benefits, which, over time, will have even greater cumulative impact:

Ahakoa he iti he pounamu Despite being small you are of great value

Final Thoughts

Natural Capital is the value and services provided to us by nature. Here in our region we boast a wide range of natural capital which provides us with a myriad of health (mental and physical), social and economic benefits and ecosystem services. However, our green areas tend to be unevenly distributed, concentrated in some areas and lacking in others. The research suggests that to achieve optimal benefits of natural capital, we need to expand nature to improve our connection with it. With ongoing resource management and infrastructure reform along with initiatives and campaigns to combat and adapt to climate change, there are various opportunities to develop strategies and direction to expand our natural capital.

Figure 4: A green Wellington (source: Relaxing Journeys NZ)

– Co-written by WSP Planners Mujahid Musa and Rachel Lawson, WSP Urban Design Leaders Anna Michels, Haley Hooper, Alan Whiteley and key members of the WSP team (WSP; Research, Urban Design, Planning, Architecture + Landscape Architecture).