Regenerative Design: bringing society and environment together to better care for our collective future.

This is article is the second in a series by WSP exploring urban design and development across Aotearoa New Zealand, and explores the vision and ideas behind ‘Regenerative Design’ and what it means for us.

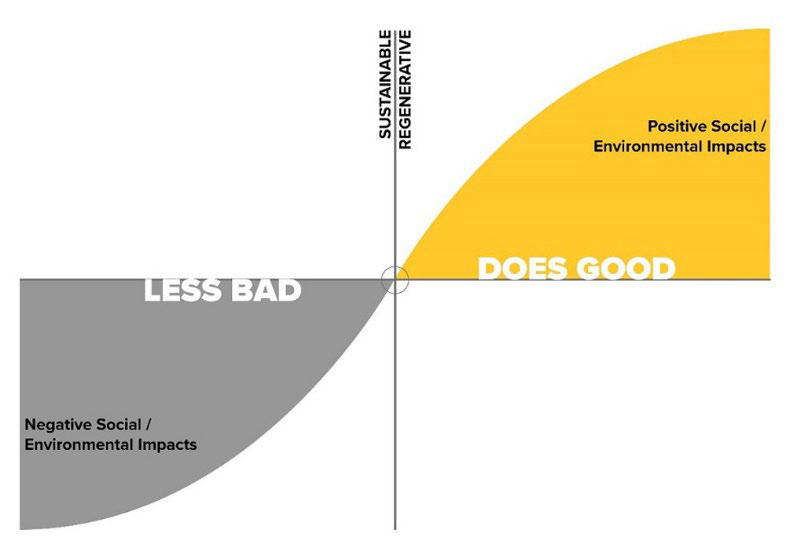

Much less bad, much more good

The world and our position in it, is a constantly evolving context and relationship. A regenerative approach invites us to see ourselves and the built environment as a responsible part of natural systems, asking us to do ‘less bad, more good.’

Through working ‘with’ our environments we can pro-actively strengthen and positively contribute to our inter-connectedness within the natural world and its cycles and eco-systems. Regenerative Design acknowledges the ongoing life cycle of environments and the necessity of helping and restoring equilibriums and enhancing places. Through this we can co-create a complex whole system of mutually reciprocal continuity between society and environment. What we plan today, we manifest tomorrow, and the future we create becomes ultimately our heritage, as well as our legacy.

Whatungarongaro te tangata toitū te whenua.

– As man disappears from sight, the land remains

Defining Regenerative Design

Regenerative Design is based on a whole living system approach to design that encompasses humanity, health and wellbeing, local economy, environment, nature, built intervention, climate and community. Regenerative Design moves beyond the forebearers of ‘regeneration’ and ‘sustainability’ that have influenced past design interests and movements.

Historically, regeneration described ‘rebuilding’ and ‘revitalising’ the built environment and communities, often following periods of redundancy, destruction or decline of large areas.

We now strive to achieve the ‘net positive’ opportunities of Regenerative Design.

Over the past decade Regenerative Design has grown as a response to increasing rates of adversity, focusing on value-generating, integrated outcomes, ecological restoration, bio-economies, green building/infrastructure and resilience. Regenerative Design is becoming more commonplace in response both to climate adversity and intentional responsivity to do better. It suggests a more continuous legacy and promotes an iterative, growing, flexible, evolving approach to designing for long-term outcomes.

Figure 1: Sustainability to Regeneration Source: Cuningham Group

Aiming for Value Add

Regenerative design is a circular system that aims to improve and add-value at every step of the life/design cycle. For example, by providing comprehensive sustainability plans, that address management of water food or waste cycles, eco-systems and biodiversity and even low-impact materiality and optimised construction methods.

As we move past patterns of linear production, consumption impact and waste towards healthier models, we recognise the interdependences and the potential of a greater systems approach. Regenerative cities and neighbourhoods focus on equity, liveability and accessibility to raise the quality of life across the board.

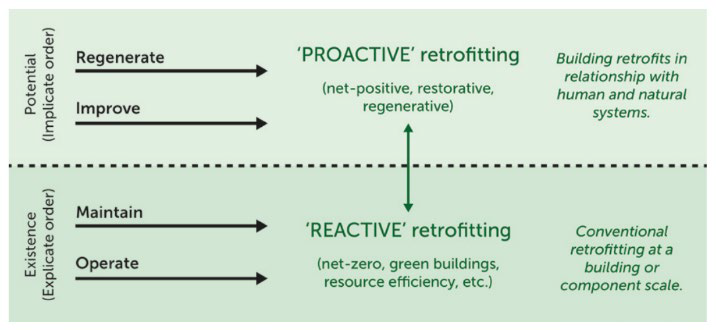

Proactive vs Reactive

The current approach to resilience has been reactive, with no notable long-term, proactive strategies for change. Regenerative design reaches further and aims beyond net-zero outcomes. It looks to pull the necessary levers at an early enough stage so that natural and built systems reap maximum benefit with minimum consumption.

Employing proactive principals in design means running projects with dynamism and adaptability to evolve as changes we cannot yet anticipate inevitably happen.

Figure 2: Proactive vs Reactive Design Source: Craft, W., Ding, L., Prasad, D., Partridge, L., & Else, D. (2017).

A deep understanding of Place

A ‘proactive’ place-based design approach enables projects to add positive value to their surroundings and work with the larger living system. By deeply considering place, the design approach is responsive and adaptive to local contexts; climate, culture and possible ways of utilising a space.

Regenerative design is derived from context, creating a need to understand the wider natural, socio, economic and cultural requirements.

In Aotearoa New Zealand our whenua (lands/places) and whakaaro (understandings/considerations) come from a layered whakapapa of place. Designing-for-place is strengthened through understanding local mana whenua priorities, pūrākau (stories) to enable the expression of cultural identity through design and huihuinga engagement. A progressively sustainable future requires us to nurture more regenerative ways of life that are interconnected with our lands, resources and ecosystems.

A Shifting Context

The connection between humans and nature can be reframed to one that considers people in nature, not separate from it.

We feel the most separated from nature in urban settings as these spaces adversely impact natural systems the most. This also means that the greatest opportunity to implement impactful change lies in the urban environment.

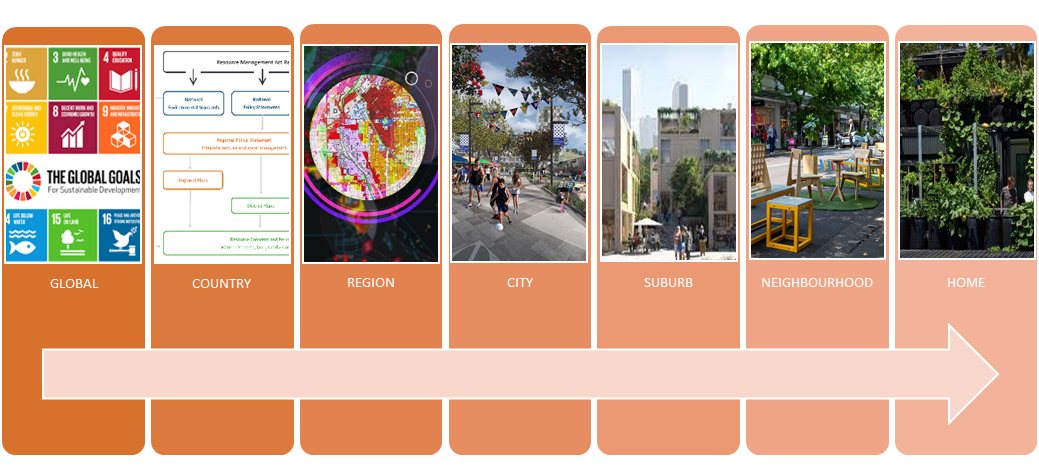

Regenerative design can be achieved at many scales across varying timeframes. At the macro end of the scale is a global approach to creating add value systems; and at the micro scale it manifests at home in your energy saving or veggie patch.

Figure 3: Regenerative Design at Different Scales Source: ALAUD

Macro to Micro Interventions

Global – Worldwide Sustainable Development Goals

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals form a global framework that highlight the convergence of key world issues and focus on improving the well-being and and co-evolution of humanity and environment, through interrelated regeneratively focused actions and outcomes.

Figure 4: Sustainable Development Goals Source: United Nations

United Nations

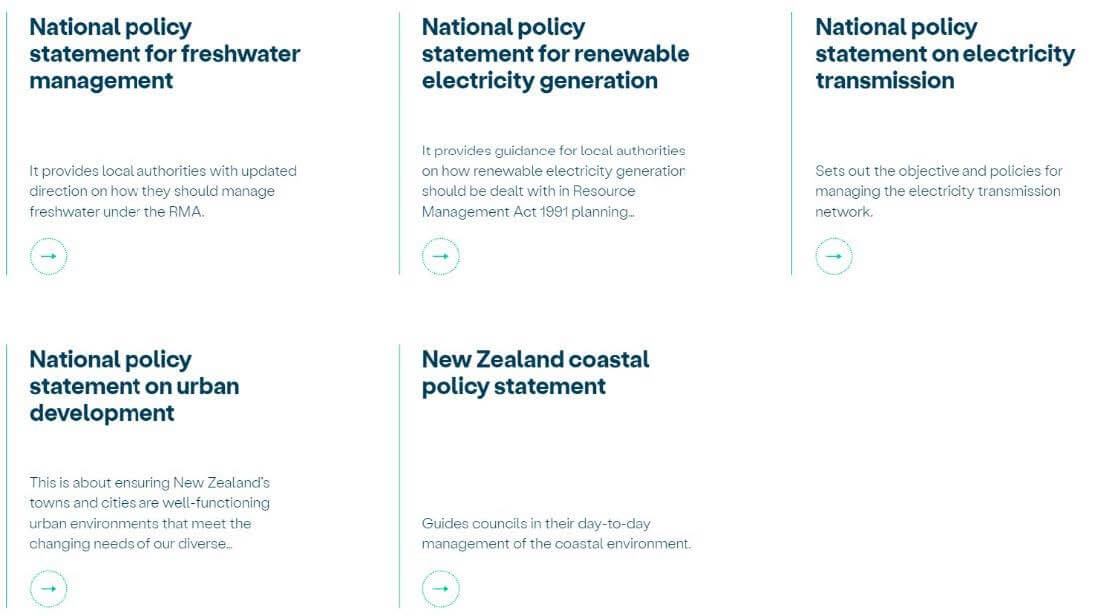

Country – National Policy Statements

Issued under the Resource Management Act, New Zealand’s national policy statements (NPS) provide a series of national directions for matters of national significance relevant to sustainable management, created as part of resource management legislative reforms. These NPS provide a national to guide the country to make national, urban and regional improvements across; freshwater, renewable electricity generation and transmission, urban development and coastal environments.

Figure 5: National Policy Statements Source: Ministry for the Environment

Regional – WSP Future Ready GIS Data Tool

When we start from the principles of understanding a place and what is needed by the people in it, we can improve both the efficiency of building processes, and the performance of the built environment, thereby decreasing the environmental impact of buildings. Part of WSP’s Future ready approach is leading the way in developing and trialling GIS data tools that allow practitioners to rationalise and improve the design and build process towards better outcomes, such as reducing material waste by reducing building size and increasing use efficiency.

These outcomes join up regionally across different buildings to connect into a regenerative system, resulting in increased collective effectiveness and overall net positive outcomes.

Citywide Strategies + Projects

At a city scale, regenerative design principles focus on creating safer, more connected, and more liveable cities. By designing cities that provide for a better quality of life, we automatically play into the regenerative design realm.

Examples of this around Aotearoa are:

• Auckland Light Rail

• Let’s Get Wellington Moving

• The Pōneke Promise

Auckland Light Rail

Light rail is more than a transport project, it’s about connecting communities. People and businesses will want to be close to stops or stations, so these areas will thrive. Developing high capacity, high quality, rapid transit is critical to developing a modern, connected city which supports improved and new public spaces, homes, shops and community facilities. When we’re easily connected to the places we want to go, we have the whole city at our feet and our quality of life improves.

Figure 6: Public Space Render Source: Auckland Light Rail

The Pōneke Promise

This is a community driven initiative to increase perceived and real safety within Wellington CBD.

Poneke Promise follows a highly engaged design process and allows space for extensive co-design to create a city that can remain adaptive into the future.

Suburb – Eco districts and Regen villages

There are countless examples of spectacular design ideas for creating a a regenerative suburb. Professionals the world over have been striving for a new brand of community that could be net-positive, resilient and adaptable.

These examples all share the same goal: to create connected communities. A well-functioning suburb that supports networks of relationships and synergies between all aspects of daily life necessities for its residents, answers the core of regenerative net-positve approach.

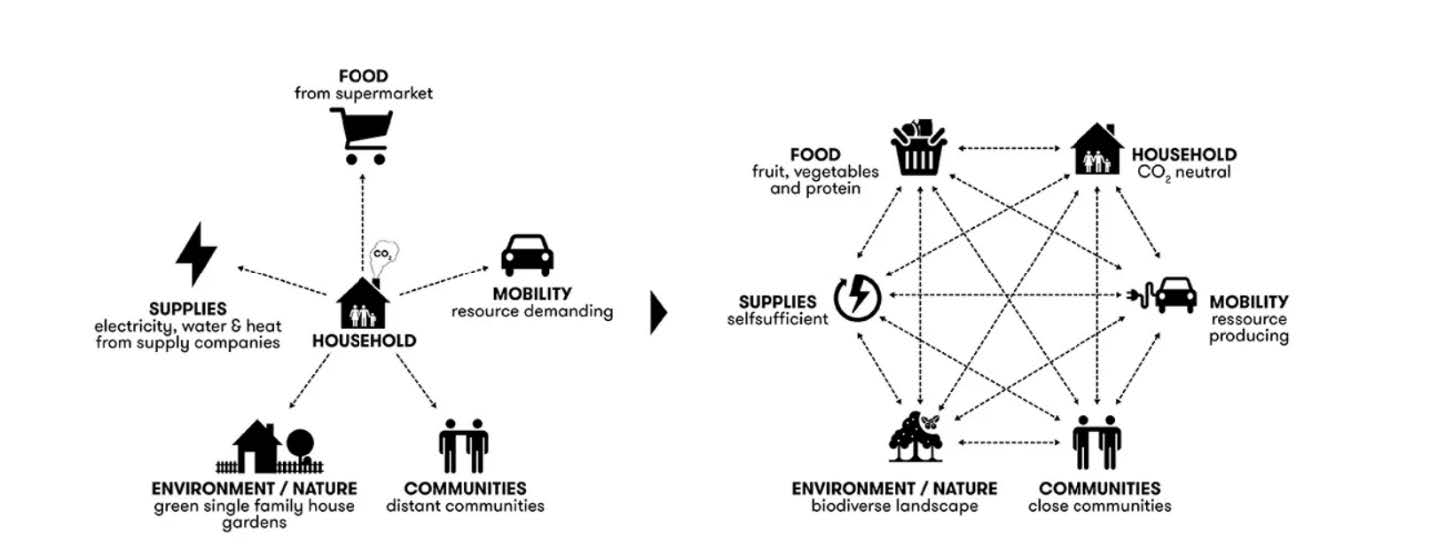

Figure 7: Inter-connected communities Source: Karres en Brands Architects

Noteworthy contributions in the discussion of what new suburbs could or already do look like are:

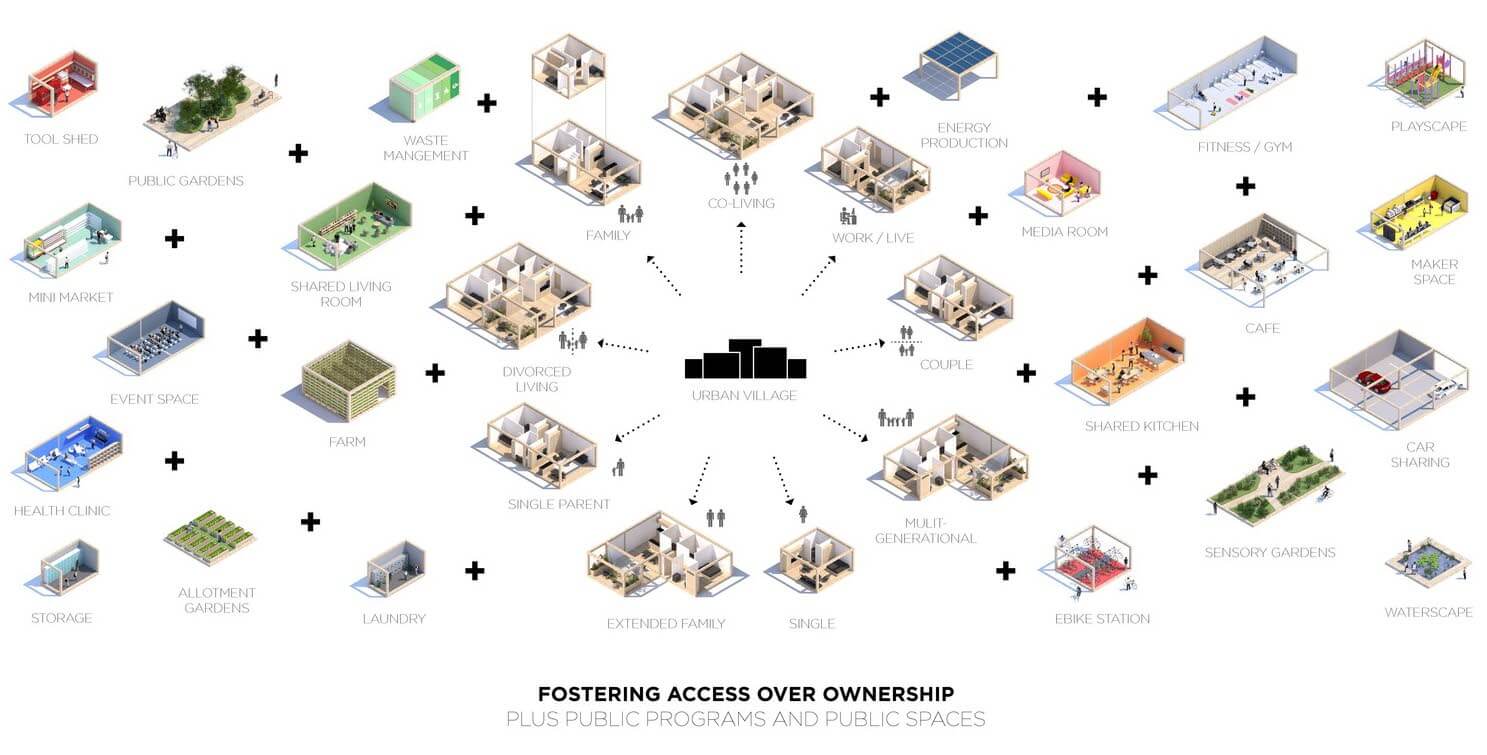

The Urban Village Project rethinks how we design, build, finance and share our future homes, neighbourhoods and cities. It aims to allow cheaper homes to enter the market, make it easier to live sustainably and affordably, and ensure more fulfilling ways of living together. It combines private living with shared spaces that enable people to be part of a vibrant community and enjoy access to a social lifestyle where they live.

Figure 8: Urban village Kit Set Source: EFFEKT Architects for SPACE10/IKEA

Barrio la Pinada, Valencia, Spain

The ‘La Pinada eco-district’ strives to co-create a suburb with a triple bottom-line lense, with no compromises on sustainability.

It embodies the regenerative design approach with a focus on multi-generational, mixed-use design, that limits its impact on natural resources.

The neighbourhood also includes the “La Mola” park of around 300 ha of rural land. The result is a healthy environment of vast green spaces surrounding each house, along with parks, green corridors, urban farms, and green wall.

Figure 9: Barrio la Pinada, Valencia, Spain. Artist impression of Eco-district Source: Sustainable Towns

Neighbourhood – tactical urbanism

Tactical urbanism is a bottom-up movement that trials a project design on the ground and avoids lengthy desktop-based design processes. If the design solution doesn’t work for the community, it can be quicky and easily adapted. Tactical urbanism projects are above all dynamic, adaptable, and rooted in place. They can be the start of a larger future system and are deeply rooted in a co-design process, making them well suited to be included within a regenerative design discussion.

Retain the adaptability of tactical urban approaches whilst moving the found design solutions into a more permanent context positions these projects as catalyst seeding longer term community initiatives and change.

Active communities that create their public spaces together create meaningful connections between residents. This promotes a sense of stewardship for the created spaces and ultimately builds a more resilient network of neighbours.

Home

Food production that can meet the needs of our populations is an ever-increasing challenge in today’s times. 58% of the world’s carbon emissions are created by our current food system. Annually, food wastage costs the global economy $940 billion. Soil exploitation has stripped essential vitamins and minerals from the food we currently eat, and global supply chain disruption have left courgettes costing $8 at the local supermarket.

Growing produce at home decreases our personal footprint, and micro-food-miles and provides us with more direct source of nutritious food. One home at a time and you may just inspire your neighbour, and the neighbour after that, and then the whole neighbourhood to create a home-based add value system that supports our familial food needs.

Figure 10: Home Grown Produce Source: Future Food Systems

Future Food Systems

Takeaways on Regenerative Design

It is vital, for future generations, that the actions we take today are in support of our world: environment and societies.

Regenerative Design represents co-creation between – and the interdependent relationship of – human and natural living systems. Globally, we are living through tumultuous times amidst huge climatic shifts. Whether it’s Christchurch experiencing a month of rain in one day, or more frequent extreme weather patterns across the planet, these experiences are the consequence of a global system failing to deliver pro-active and positive change at the rate necessary to address the issues we are all facing.

Focusing on ‘lessening’ negative impacts but ‘continuing’ to create negative impacts is no longer good enough. We need zero-impact to be the minimum, and a transition towards net-positive impacts (putting more into the environment and society than we take out), resulting in ecological gains. We can achieve through regenerative design principles, which enable a whole system move towards a circular approach. Increasingly, people are shifting away from the mindset of ‘people and nature’ as separate entities, towards the power of ‘people-in-nature’ as one entity.

A regenerative system adds-value and offers feedback loops which allow for adaptability, dynamism and emergence to create and develop highly resilient and flourishing eco-systems that positively contribute to the environment and its communities.

At the core of regenerative design is the recognition that the practice goes beyond measuring the environmental, social, cultural and economic impacts of sustainable design, to a focus on reciprocity. A reciprocity where we can grow a network of interwoven environmental and societal benefits that positively support the regenesis of our local places, for Aotearoa and for our world.

– Co-written by WSP Urban Design Leaders Anna Michels, Haley Hooper, Alan Whiteley and key members of the WSP team (WSP; Research, Urban Design, Planning, Architecture + Landscape Architecture)

In the next edition of our five part series into Spatial Planning with Wellington Regional Growth, we will provide discussion on ‘Natural Capital in our Capital’, and talk about the importance of biodiversity networks, environment, resources, nature, communities and landscapes in placemaking for Wellington and its regions.